Study Finds Racial Disparities in Access to New Mammography Technology

Released: October 11, 2022

At A Glance

- Black women had less access to new mammography technology than white women, according to a study of over 4 million Medicare mammography claims from 2005 to 2020.

- The study found evidence of racial differences in the years following the introduction of newer mammography technology.

- Black women are 40% more likely than white women to die from breast cancer.

- RSNA Media Relations

1-630-590-7762

media@rsna.org

OAK BROOK, Ill. — Among the Medicare population from 2005 to 2020, Black women had less access to new mammography technology compared with white women, even when getting their mammograms at the same institution, according to a study of over 4 million claims published in Radiology, a journal of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Black women are 40% more likely than white women to die from breast cancer, even though the cancer incidence rate among Black and white women is approximately the same.

Mammographic technology used to screen for breast cancer has undergone two major transitions since 2000: first, the transition from screen-film mammography (SFM) to full-field digital mammography (FFDM) and second, the transition to digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT). While these advances in early detection mean that more women can survive breast cancer, not all women have equal access to these newer technologies.

More sufficient, initial Medicare coverage can aid access to new breast cancer screening technologies in underserved areas and reduce the duration of related racial and regional breast cancer care disparities. Such disparities are transitory and eventually ease as technology dissipates from affluent areas – with more private insurance coverage – to underserved communities where public insurance may be more prevalent. However, this process is prolonged by Medicare reimbursement that is 1.2 to 1.8 times lower than that of private insurers.

“In the increasingly competitive healthcare environment, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) cannot expect medical providers to ignore these competitive forces and engage in health equity efforts without regard for the economic consequences by locating technology and services where reimbursement is low,” said study co-author Eric W. Christensen, Ph.D., principal research scientist in health economics for the Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute and adjunct professor of health services management at The University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. “Inequities result when lower payments make technology investments economically unsustainable for practices that serve higher proportions of Medicare patients.”

The study was the work of the Neiman Health Policy Institute in collaboration with the Radiology Health Equity Coalition (RHEC), an initiative of 10 major radiology organizations to positively impact health care equity.

“The Radiology Health Equity Coalition understands the indispensable role research plays in addressing health disparities,” said study co-author Jinel Scott, M.D., M.B.A., associate professor of clinical radiology in the Department of Radiology at State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University, and chief quality officer at New York Health and Hospitals/Kings County, in New York City. “Our paper is an example of the coalition’s goal to evolve from predominantly descriptive analyses to predictive and ultimately prescriptive approaches to combating the patient outcomes that are related to inequities in health care delivery.” An at-large director on the RSNA Board of Directors, Dr. Scott serves as RSNA’s representative to the RHEC.

For the study, Dr. Christensen, Dr. Scott and colleagues set out to examine the relationship between race and use of newer mammographic technology in women receiving mammography services.

The researchers conducted a retrospective study of women aged 40-89 with Medicare fee-for-service insurance who got mammograms between January 2005 and December 2020, using a 5% sample of all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.

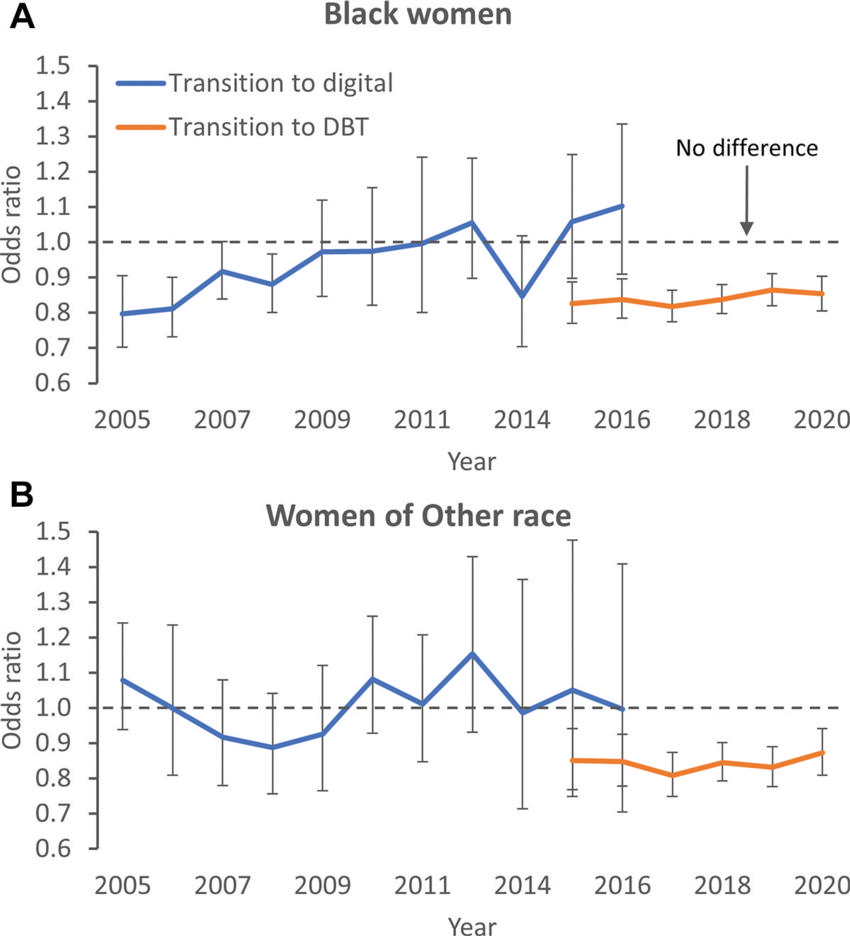

The researchers analyzed 4,028,696 institutional mammography claims for women (mean age 72 years). Within an institution, the odds ratio (OR) of Black women receiving digital mammography rather than SFM in 2005 was 0.80 when compared with white women. These differences remained until 2009. Compared with white women, the use of DBT within an institution was less likely for Black women from 2015 to 2020 (OR: 0.84).

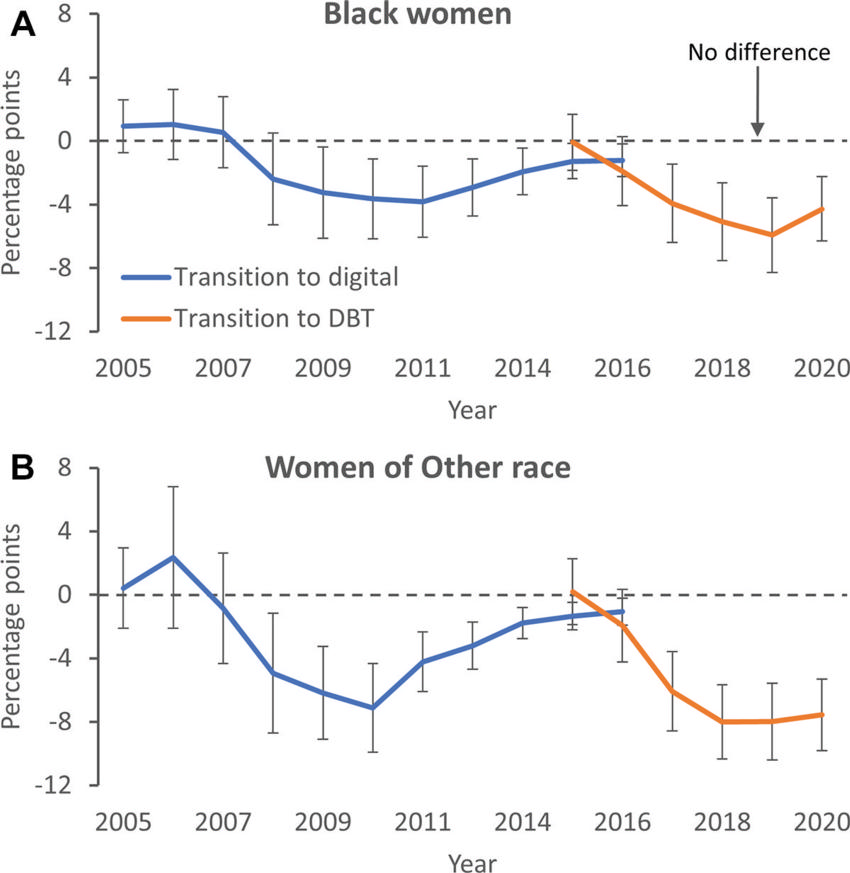

Across institutions, there were racial differences in digital mammography use, which peaked at 3.8 percentage points less for Black compared with white women in 2011 and then decreased to 1.2 percentage points less in 2016. These results show the transitory nature of these differences, and while the transition to DBT is still underway, those differences also appear to be subsiding.

The study found evidence of racial differences in the years following the introduction of newer mammography technology. These disparities include both within institution and comparable-institution differences. According to Dr. Christensen, advocacy for favorable reimbursement and incentive policies may diminish these differences if kept apace of evolving technologies.

“Current reimbursement contributes to inequity because locating new technology in facilities that serve patients with public insurance, Medicare and Medicaid, is not economically sustainable,” he said. “CMS can create economic incentives to lessen disparities through reimbursement that is either comparable to private payers or that more directly incentivizes adoption of newer technology in underserved communities.”

The researchers stipulate that organizations have a responsibility to be equitable in the provision of care. The ability for them to do so will be enhanced by reimbursement policies that facilitate investing in sites that serve disadvantaged individuals. The fact that the racial differences for digital mammography were transitory and subsided as new technology became universal supports the real potential for such policy changes to mitigate transitional disparities associated with technological advances. Equitable provision of breast cancer screening has the potential to improve population health and supporting health policy can propel the U.S. health care system closer to this goal.

The RHEC includes RSNA, ACR, American Board of Radiology, American Medical Association Section Council on Radiology, Association of University Radiologists, National Medical Association Section on Radiology and Radiation Oncology, Society of Chairs of Academic Radiology Departments, Society of Interventional Radiologists, Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging and American Association of Physicists in Medicine. Several other groups, including specialty and state radiology organizations, have also joined the initiative as Coalition partners.

“The RSNA supports the work of the RHEC and values an intersociety approach that provides members with the information and tools needed to be advocates for the communities they serve,” Dr. Scott said.

“Relationship between Race and Access to Newer Mammographic Technology in Women with Medicare Insurance.” Collaborating with Drs. Christensen and Scott were Mikki Waid, Ph.D., Bhavika K. Patel, M.D., Jacqueline A. Bello, M.D., and Elizabeth Y. Rula, Ph.D.

Radiology is edited by David A. Bluemke, M.D., Ph.D., University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin, and owned and published by the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. (https://pubs.rsna.org/journal/radiology)

RSNA is an association of radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists and related scientists promoting excellence in patient care and health care delivery through education, research and technologic innovation. The Society is based in Oak Brook, Illinois. (RSNA.org)

The Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute, established by the American College of Radiology (ACR.org), studies the value and role of radiology and radiologists in evolving health care delivery and payment systems. Neiman Institute research provides a foundation for evidence-based imaging policy to improve patient care and bolster efficient, effective use of health care resources. (NeimanHPI.org)

For patient-friendly information on breast imaging, visit RadiologyInfo.org.

Media Contacts:

RSNA

Linda Brooks

630-590-7738

LBrooks@rsna.org

Neiman Health Policy Institute

Nichole Gay

703-648-1665

ngay@neimanhpi.org

Images (JPG, TIF):

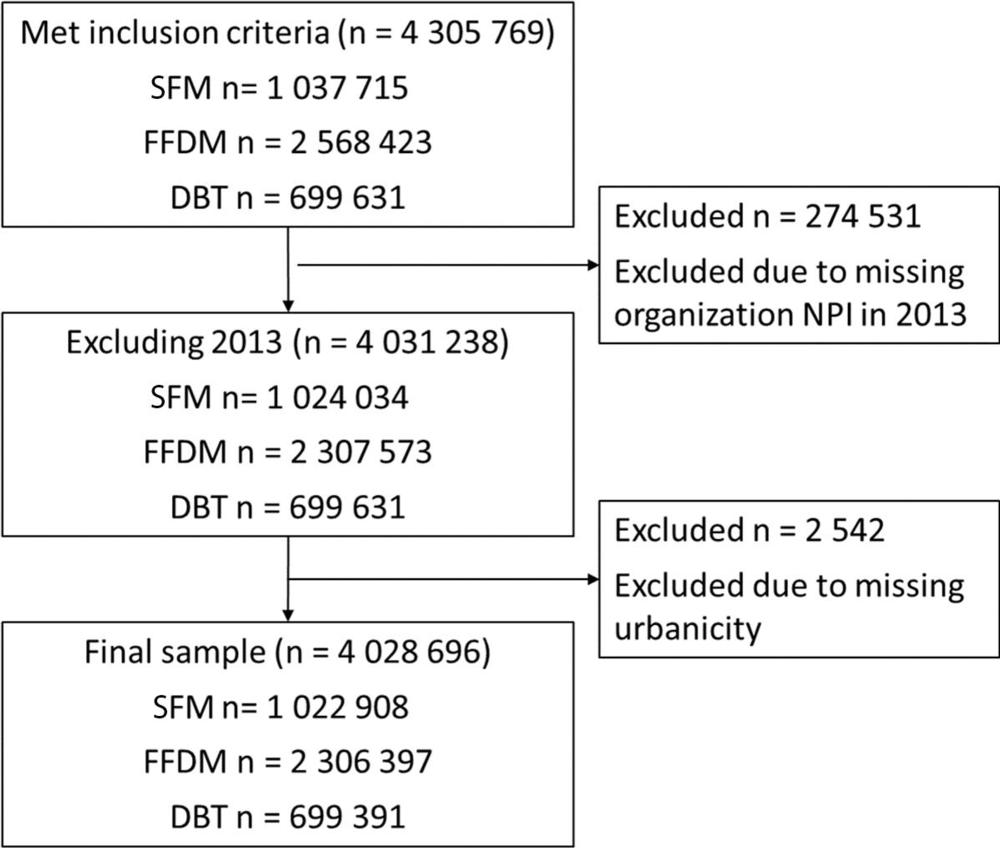

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the data inclusion and exclusion criteria and the number of women who underwent imaging with each mammographic technology. DBT = digital breast tomosynthesis, FFDM = full-field digital mammography, NPI = National Provider Identifier, SFM = screen-film mammography.

High-res (TIF) version

(Right-click and Save As)

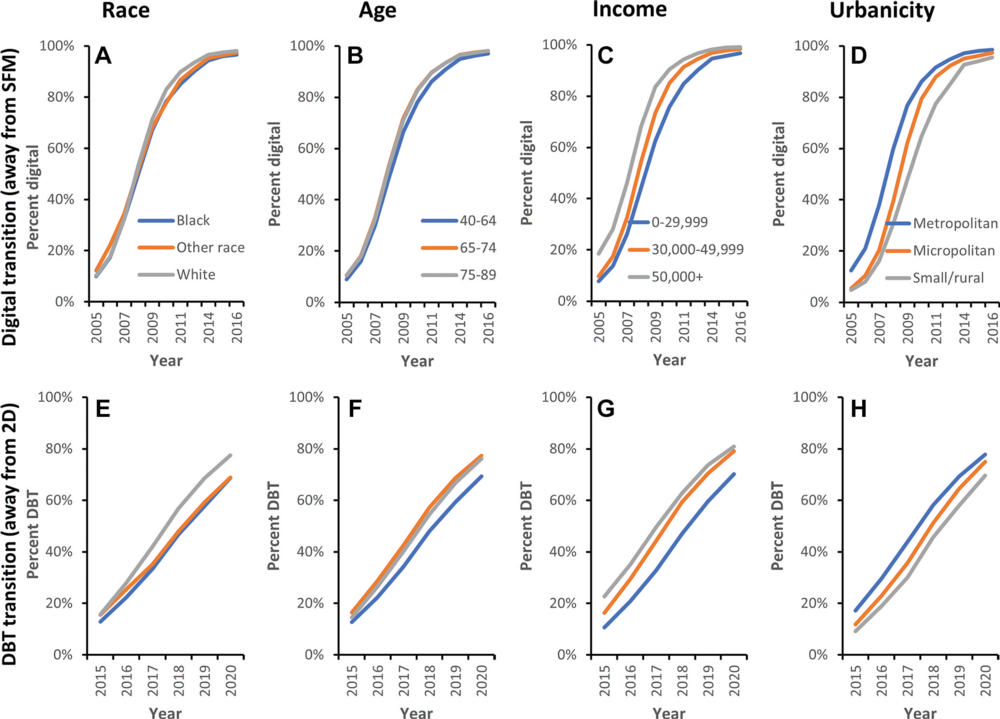

Figure 2. Graphs show unadjusted patient characteristics for newer mammographic imaging transitions from 2005 to 2020 according to (A, E) race, (B, F) age, (C, G) income, and (D, H) urbanicity. “Other” race includes Asian, Hispanic, North American Native, and other. DBT = digital breast tomosynthesis, SFM = screen-film mammography, 2D = two-dimensional mammography.

High-res (TIF) version

(Right-click and Save As)

Figure 3. Graphs show odds ratios according to race for receiving newer mammographic imaging at the same institution (within-institution differences) from 2005 to 2020 for (A) Black compared with White women and (B) women of other race compared with White women. For the transition to digital mammography (full-field digital mammography [FFDM] or digital breast tomosynthesis [DBT]), there was a difference for Black compared with White women until 2009 and no difference for women of other race. For the transition to DBT, there were differences for both Black women and women of other race. For the transition to the digital model (2005–2016), newer technology was defined as FFDM or DBT. For the transition to the DBT model (2015–2020), newer technology was defined as DBT only. Other race includes Asian, Hispanic, North American Native, and Other. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

High-res (TIF) version

(Right-click and Save As)

Figure 4. Graphs show percentage-point differences according to race for receiving mammography at an institution with equal capability for newer mammographic imaging (comparable-institution differences) from 2005 to 2020 for (A) Black compared with White women and (B) women of other race compared with White women. For the transition to digital mammography, there was a pattern of deepening racial differences as the transition progressed followed by decreasing racial differences as digital became universal. For the transition to digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), there was a similar pattern of deepening racial differences and the beginning of decreasing differences as DBT has become more prevalent. For the transition to the digital model (2005–2016), newer technology was defined as full-field digital mammography or DBT. For the transition to the DBT model (2015–2020), newer technology was defined as DBT only. Other race includes Asian, Hispanic, North American Native, and other. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

High-res (TIF) version

(Right-click and Save As)